How to do thematic Analysis for your research

Wondering about how to do thematic Analysis for your research for your PhD thesis or MBA dissertation? Thematic analysis is the process of identifying patterns or themes within qualitative data. Braun & Clarke (2006) suggest that it is the first qualitative method that should be learned as ‘..it provides core skills that will be useful for conducting many other kinds of analysis’ (p.78). A further advantage, particularly from the perspective of learning and teaching, is that it is a method rather than a methodology (Braun & Clarke 2006; Clarke & Braun, 2013). This means that, unlike many qualitative methodologies, it is not tied to a particular epistemological or theoretical perspective. This makes it a very flexible method, a considerable advantage given the diversity of work in learning and teaching.

There are many different ways to approach thematic analysis (e.g. Alhojailan, 2012; Boyatzis,1998; Javadi & Zarea, 2016). However, this variety means there is also some confusion about the nature of thematic analysis, including how it is distinct from a qualitative

content analysis (Vaismoradi, Turunen & Bonda, 2013). In this example, we follow Braun & Clarke’s (2006) 6-step framework. This is arguably the most influential approach, in the social sciences at least, probably because it offers such a clear and usable framework for doing thematic analysis.

The goal of a thematic analysis is to identify themes, i.e. patterns in the data that are important or interesting, and use these themes to address the research or say something about an issue. This is much more than simply summarising the data; a good thematic analysis interprets and makes sense of it. A common pitfall is to use the main interview questions as the themes (Clarke & Braun, 2013). Typically, this reflects the fact that the data have been summarised and organised, rather than analysed.

Braun & Clarke (2006) distinguish between two levels of themes: semantic and latent. Semantic themes ‘…within the explicit or surface meanings of the data and the analyst is not looking for anything beyond what a participant has said or what has been written.’ (p.84). The analysis in this worked example identifies themes at the semantic level and is representative of much learning and teaching work. We hope you can see that analysis moves beyond describing what is said to focus on interpreting and explaining it. In contrast, the latent level looks beyond what has been said and ‘…starts to identify or examine the underlying ideas, assumptions, and conceptualisations – and ideologies – that are theorised as shaping or informing the semantic content of the data’ (p.84). Here are the steps for how to do thematic Analysis for your research!

Step 1 of Thematic analysis : Become familiar with the data.

The first step in any qualitative analysis is reading, and re-reading the transcripts. The interview extract that forms this example can be found in Appendix 1. You should be very familiar with your entire body of data or data corpus (i.e. all the interviews and any other data you may be using) before you go any further. At this stage, it is useful to make notes and jot down early impressions. Below are some early, rough notes made on the

extract: The students do seem to think that feedback is important but don’t always find it useful. There’s a sense that the whole assessment process, including feedback, can be seen as threatening and is not always understood. The students are very clear that they want very specific feedback that tells them how to improve in a personalised way. They want to be able to discuss their work on a one-to-one basis with lecturers, as this is more personal and also private. The emotional impact of feedback is important.

Step 2 of Thematic analysis : Generate initial codes.

In this phase we start to organise our data in a meaningful and systematic way. Coding reduces lots of data into small chunks of meaning. There are different ways to code and the method will be determined by your perspective and research questions. We were concerned with addressing specific research questions and analysed the data with this in mind – so this was a theoretical thematic analysis rather than an inductive one. Given this, we coded each segment of data that was relevant to or captured something interesting about our research question. We did not code every piece of text. However, if we had been doing a more inductive analysis we might have used line-by-line coding to code every single line. We used open coding; that means we did not have pre-set codes, but developed and modified the codes as we worked through the coding process. We had initial ideas about codes when we finished Step 1. For example, wanting to discuss feedback on a one-to one basis with tutors was an issue that kept coming up (in all the

interviews, not just this extract) and was very relevant to our research question. We discussed these and developed some preliminary ideas about codes. Then each of us set about coding a transcript separately. We worked through each transcript coding every segment of text that seemed to be relevant to or specifically address our research question. When we finished we compared our codes, discussed them and modified them before moving on to the rest of the transcripts. As we worked through them we generated new codes and sometimes modified. existing ones. We did this by hand initially, working through hardcopies of the transcripts with pens and highlighters. Qualitative data analytic software (e.g. ATLAS, Nvivo , MAXQDA etc.), if you have access to it, can be very useful, particularly with large data sets. Other tools can be effective also; for example, Bree & Gallagher (2016) explain how to use Microsoft Excel to code and help identify themes. While it is very useful to have two (or more) people working on the

coding it is not essential. In Appendix 2 you will find the extract with our codes in the margins.

Step 3 of Thematic analysis : Search for themes.

As defined earlier, a theme is a pattern that captures something significant or interesting about the data and/or research question. As Braun & Clarke (2006) explain, there are no hard and fast rules about what makes a theme. A theme is characterised by its significance. If you have a very small data set (e.g. one short focus-group) there may be considerable overlap between the coding stage and this stage of identifying preliminary themes. In this case we examined the codes and some of them clearly fitted together into a theme. For example, we had several codes that related to perceptions of good practice and what students wanted from feedback. We collated these into an initial theme called The purpose of feedback.

At the end of this step the codes had been organised into broader themes that seemed to say something specific about this research question. Our themes were predominately descriptive, i.e. they described patterns in the data relevant to the research question. Table 2 shows all the preliminary themes that are identified in Extract 1, along with the codes that are associated with them. Most codes are associated with one theme although some, are associated with more than one (these are highlighted in Table 2). In this example, all of the codes fit into one or more themes but this is not always the case and you might use a ‘miscellaneous’ theme to manage these codes at this point.

Step 4 of Thematic analysis : Review themes.

During this phase we review, modify and develop the preliminary themes that we identified in Step 3. Do they make sense? At this point it is useful to gather together all the data that is relevant to each theme. You can easily do this using the ‘cut and paste’ function in any word processing package, by taking a scissors to your transcripts or using something like Microsoft Excel (see Bree & Gallagher, 2016). Again, access to qualitative data analysis software can make this process much quicker and easier, but it is not essential. Appendix 3 shows how the data associated with each theme was identified in our worked example. The data associated with each theme is colour-coded. We read the data associated with each theme and considered whether the data really did support it. The next step is to think about whether the themes work in the context of the entire data set. In this example, the data set is one extract but usually you will have more than this and will have to consider how the themes work both within a single interview and across all the interviews.

Themes should be coherent and they should be distinct from each other. Things to think about include:

• Do the themes make sense?

• Does the data support the themes?

• Am I trying to fit too much into a theme?

• If themes overlap, are they really separate themes?

• Are there themes within themes (subthemes)?

• Are there other themes within the data?

For example, we felt that the preliminary theme, Purpose of Feedback ,did not really work as a theme in this example. There is not much data to support it and it overlaps with Reasons for using feedback(or not) considerably. Some of the codes included here (‘Unable to judge whether question has been answered/interpreted properly’) seem to relate to a separate issue of student understanding of academic expectations and assessment criteria. We felt that the Lecturers theme did not really work. This related to perceptions of lecturers band interactions with them and we felt that it captured an aspect of the academic environment. We created a new theme Academic Environment that had two subthemes: Understanding..

Step 5 of Thematic analysis : Define themes.

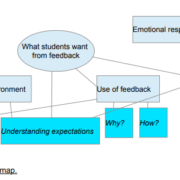

This is the final refinement of the themes and the aim is to ‘..identify the ‘essence’ of what each theme is about.’.(Braun & Clarke, 2006, p.92). What is the theme saying? If there are subthemes, how do they interact and relate to the main theme? How do the themes relate to each other? In this analysis, What students want from feedback is an overarching theme that is rooted in the other themes. Figure 1 is a final thematic map that illustrates the relationships between themes and we have included the narrative for What students want from feedback below.

Step 6 of Thematic analysis: Writing-up.

Usually the end-point of research is some kind of report, often a journal article or dissertation. Table 4 includes a range of examples of articles, broadly in the area of learning and teaching, that we feel do a good job of reporting a thematic analysis.

Do you want help on How to do thematic Analysis for your research?

Email/Gmeet: dissertationshelp4u@gmail.com

Whatsapp/IMO/Call: +91.9830529298

#research #thematic #analysis #PhD #MBA #interview #interviewanalysis #transcript #nVIVO #nVIVOanalysis #MAXQDA #MAXQDAanalysis thematicanalysis in dissertation, thematicanalysis in thesis, thematicanalysis in MBA, thematicanalysis in Scotland dissertation, thematicanalysis in Ireland dissertation, thematicanalysis in Germany dissertation, thematicanalysis in Austria dissertation, thematicanalysis in Hungary dissertation, nVIVOanalysis Scotland, nVIVOanalysis Ireland, nVIVOanalysis Germany, nVIVOanalysis Hungary, nVIVOanalysis Austria